By Delbert Voight, Extension Agronomist

Potassium (K) occurs in the soil in three forms: as exchangeable (available) potassium (K+) adsorbed onto the soil CEC; fixed by certain minerals from which it is released very slowly to available form; and in unavailable mineral forms (most of the K in soils, often 40,000 pounds per acre or more).

Plants take up K as the K+ ion. Over time “slowly available K” is released, replacing exchangeable K; however, plants cannot use much of this form of K in a single growing season.

Potassium has a role in the plant physiology and chemistry with movement of water, nutrients and carbohydrates within the plant. Potassium will stimulate early growth, increase protein production, improve water use efficiency, and improve resistance to diseases and insects as established in several studies in the Agronomy Journal.

Plants with insufficient K result in more drought stress and have a more difficult time in absorbing water and nitrogen (N) from the soil, which can increase drought stress. The crop plants have the ability of closing leaf stomata — small pin holes in the lower leaf responsible for gas exchange. By closing and opening the stomata, the plants can regulate the amount of water conserved. This is all regulated by K. At low levels of K the stomata do not close, which reduces the ability of the plant to minimize drought stress.

Potassium is between N and phosphorus (P) in mobility. It is not lost as readily as N, but it will move into the soil to the roots more quickly than P.

Potassium fertilizers are most effective if applied ahead of planting or as topdressing on perennial forage crops. Because of the salt concern, the amount of K that can be safely applied in a starter band is limited. The rule of thumb for salt injury is no more than 70 pounds of N + K20 should be applied in a band within 2 inches of the seed, or no more than 10 pounds of N + K20 should be applied directly with the seed.

If a K deficiency is observed after planting, topdressing of K fertilizer can somewhat — and in my experience — completely overcome the deficiency. Even if the impact on the current crop is limited, if there is a deficiency, the K will need to be applied at some point, so it is best to go ahead and topdress some K fertilizer to get what immediate benefit you can and get a head start on building the K in the soil back up into the optimum range.

The two pictures of soybeans and corn included in this article that showed deficiency had 120 pounds of K20 (200 pounds of 0-0-60) applied the same day as I inspected the field, and the symptoms were gone completely within a week.

One additional consideration with K deficiency is that compaction can often result in K deficiency, even in a soil testing optimum or higher. A soil test should be taken to make sure the problem is low soil K before topdressing in these situations.

This season at one of the Pennsylvania Soybean On Farm Network farms, we observed K deficiency. Here is a brief video describing the situation.

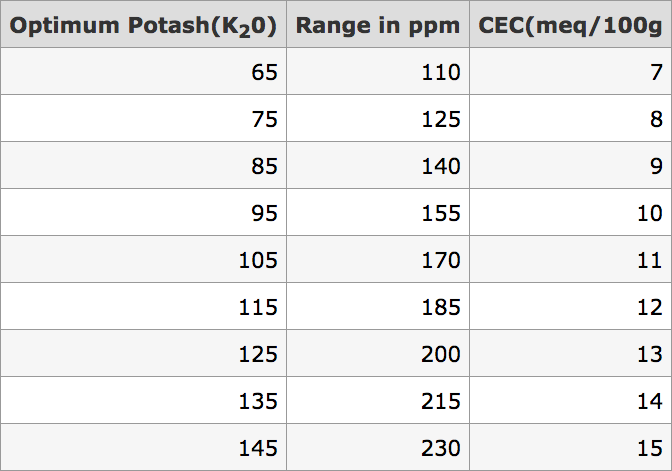

Below are some optimum ranges for K20 that are used to make recommendations. The optimum level of potash is 2-3.3% of the soil cation exchange capacity (CEC), and thus the optimum level will vary by the soil type and management, and will need to be adjusted as no-till and cover cropping increases the CEC in the soil. Penn State agronomist Doug Beegle calibrated the recommendations based on Pennsylvania soils in different climatic areas, and has found the following levels to base management decisions on.

On the Penn State Soil Test results, growers can observe the bar chart to determine if the soil is in the optimum level, and/or observe the CEC and the percent saturation of K at the lower portion in the lab results. If at the optimum level, growers need to account for the removal of K during the season.

This table below best describes how some fields can quickly become deficient and hence loss of yield occurs. It is also useful in explaining why the tremendous yields being recorded may result in large amounts of potassium inputs being required to maintain high end yields.

‘K’ Application Timing

As growers fine tune K applications, it is best to time prior to planting, or more recently based on some Agronomy Journal research, split applications impacting the grain quality. As we move into fall there are some environmental tests illustrating the physical movement of K from fields into water bodies with heavy rains that may result shortly after applications. In the future there may be limits on applying K in the fall.

Effect of no-till surface broadcast P2O5 and K2O rates applied in spring 2012 and 2013 on corn grain yield at Arlington, Wis.

Effect of no-till surface broadcast P2O5 and K2O rates applied in spring 2012 and 2013 on corn grain yield at Arlington, Wis.

Sources of 'K' to Correct Soils

There are many ways to correct soil K deficiency. Manure, compost and commercial fertilizers will all supply adequate K inputs to correct soil issues.

In the Lebanon area, there were three scenarios where growers had corn that lodged from stalk rot pathogens. The lodged areas were soil tested and compared to normal corn. In all three scenarios, a history of manure resulted in the field having areas far from the home farm that hadn’t received as much manure over time, resulting in whole field soil test results in the optimum range, while the farthest areas were severely deficient.

The most widely used product is Muriate of Potassium (0-0-60). As a source, muriate (really a misnomer, it should be called KCL) of Potash (0-0-60) is a great source to correct deficiencies in the soil as well as in season deficiencies. There are times when soils are adequate, however the roots might not get to the nutrient either from compaction and/or other drought times. In these cases either dry and or liquid foliar applications might be useful.

However, if a deficiency is caused by low soil level K, then foliar liquids are not economical to correct the soil issues. They will bring the plant out of the deficiency for a short time.

This season we had a deficiency at an On Farm site and used 1 gallon per acre of a foliar K product. It really greened up the plants. But in as little as 2 months, the plants displayed symptoms again. This further supports two prongs: correct the soil K levels and tissue to test to begin correcting with foliar products any hidden deficiency.

I did find a correlation to applied rates from a recent Pioneer study. The soil test results were in the low range for both P and K. The point is to understand that results of applications and recommendations from Penn State and others are based on the fact that the grower will realize a return in bushels per acre by managing soil fertility.

Take Home Message

- Soil K levels are critical to plant health and optimum growth.

- Soil testing methods can change the results of measurable soil K levels.

- Calibration of soil testing methods are specific to Pennsylvania conditions.

- Application timing of K to fields can impact growth and development.

- Sources of K vary by material and price. It is important to ensure the proper applied rate is determined once the amount of K20 is determined by soil testing and/or removal calculations.

- Foliar K applications are useful in dry conditions and when soil K levels are maintained