By Jo Craven McGinty, The Wall Street Journal

An unusual workforce labors beneath the surface of the world’s farms.

It can turn over 8,000 pounds of earth on an acre of land in two weeks. Its tunnels aerate the soil, and its castings nourish it.

Not bad for invertebrates the size of a string bean.

They are earthworms, the industrious wigglers Charles Darwin once called nature’s plow. But farmers’ plows have been killing the tiny tillers for decades, leaving cropland less fertile and increasing the need for chemical nutrients.

A new study confirms the impact of conventional plowing and evaluates the effects of alternative tilling methods.

“Conventionally plowed soils reduce earthworm populations drastically, and this means that we get few of the good things that earthworms do for us,” said Maria J.I. Briones, an author of the study and a professor of soil zoology at Universidad de Vigo in Spain.

Earthworm populations can bounce back if conventional plowing is replaced with less disruptive methods, but there are trade-offs.

Conventional tillage, which disrupts soil to a depth of 8-16 inches, provides crops with optimal conditions for germination and inhibits weeds, pests and disease.

Conventional tillage, which disrupts soil to a depth of 8-16 inches, provides crops with optimal conditions for germination and inhibits weeds, pests and disease.

Conservation methods — such as no till or strip till that forgo plowing or limit it to shallow depths in targeted areas — reduce fuel and labor costs and the need for chemical fertilizers, but crop yields may shrink and the need for herbicides may increase.

“When you use no till or reduced till, you put less energy and less work into the system,” said David Jones, a biologist and earthworm expert at the Natural History Museum in London. “It’s not surprising that yield might drop, but it benefits the soil and the long-term sustainability of agriculture. You have to look at what you want to achieve in the long term.”

Earthworms improve the structure and fertility of soil by working organic material into the dirt, providing channels that make it easier for water and oxygen to penetrate it and converting nutrients into forms plants can readily absorb. When the population of the worms is diminished, the quality of the soil suffers.

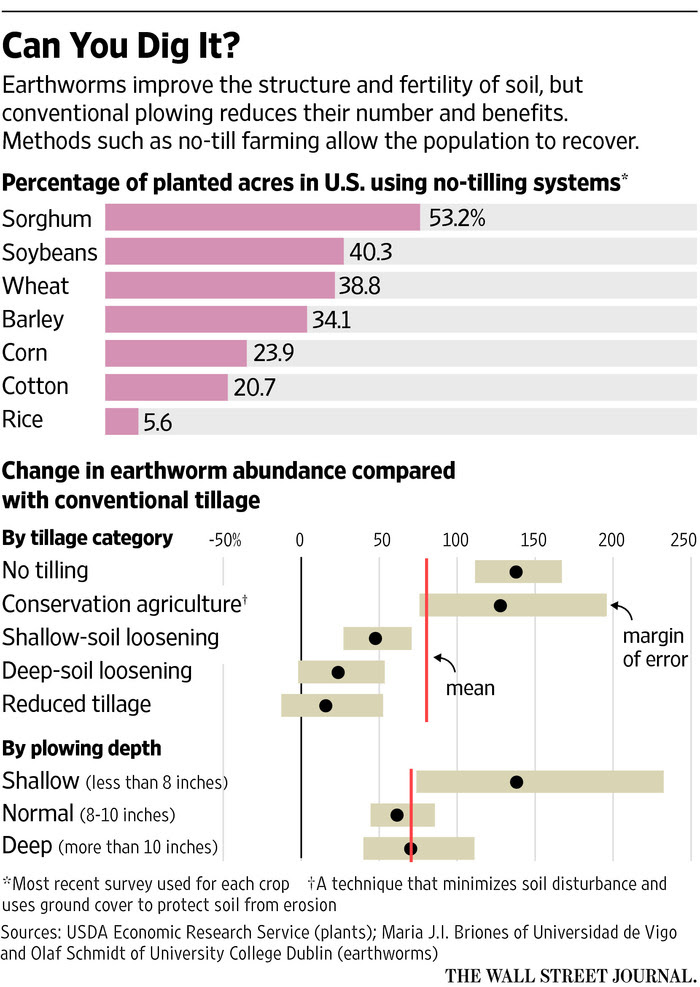

To gauge the extent of the problem, Dr. Briones and Olaf Schmidt, a professor in the school of agriculture and food science at University College in Dublin, reviewed 215 field studies from 40 countries dating back to 1950.

Their research, published in the scientific journal Global Change Biology, found declining populations in fields that were plowed every year. Disturbing the soil less increased abundance up to 137%.

Conventional plowing kills earthworms through injury or by exposing them to predators, destroying their burrows and diminishing their food supply.

“The more you till, the less they have to eat,” said Sharon Weyers, a soil scientist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A good earthworm population might number around 200 worms per square meter. An excellent population would have twice as many.

“If you’ve got more than 400 earthworms per meter squared, you are more likely to have best improvement in crop yield,” Dr. Jones said. “The more worms you have, the better.”

Earthworm Watch, a collaboration of the Earthworm Society, London’s Natural History Museum and Earthwatch Institute, monitors earthworms and soil health in the U.K. There is no comparable survey in the U.S., but individual research projects assess earthworm populations.

To count worms, researchers dig a pit around 1 cubic foot in size, then sift through the soil by hand, or they roust worms from the ground by sending electroshocks through the soil or by soaking it with a solution of hot mustard. Irritated earthworms surface, where they can be counted.

It can take a decade or more for diminished populations to rebound, Drs. Briones and Schmidt found, with populations increasing the most when the soil is disturbed the least.

No-till farming, which is used on about 34% of cropland in the U.S., according to USDA economist Steven Wallander, is the least disruptive.

Although no-till farming is theoretically possible on most cropland, the cost of changing to specialized seeding equipment may be prohibitive for small farms, which populate much of the world.

John Ledermann, a third-generation Minnesota farmer who raises corn, soybeans, wheat and cereal rye, has transitioned his 1,100 acres to no-till and strip-till.

His yields have been mixed, he said, but he’s using about half the fuel and sees visible improvements to the soil.

He recalled walking across a field at dusk one spring when he noticed movement on the ground.

“The earthworms had come up,” he said. “As I walked along, they were flicking back in their burrows. You wouldn’t believe how fast they could move.”