“A nation that destroys its soil, destroys itself,” said Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Dust Bowl era. Strip-tillers are acutely aware of the need to maintain productivity while conserving soil with practices like cover cropping, but finding time to manage cover crops annually can be a big challenge. The concept of perennial groundcover (PGC) systems, where a perennial cover crop is planted once and then remains for multiple years alongside annual cash crops, could be an easier path to cover crop integration for strip-tillers.

In PGC systems, under most conditions, the established perennial is strip-tilled before planting the main crop, whether corn or soybeans. If successfully established, the result is an inter-row sward, or grassy surface, capable of providing year-round ground cover, holding down soil on sloping fields, enhancing carbon sequestration, contributing microbial diversity to the soil and suppressing weeds. Over time the initial seeding fills in between the rows. The perennial sward remains from year to year, and the cash crop is planted into the strips. Strips are freshened each year, along with fertilization, other amendments and in-row weed control.

Raj Raman, professor in Ag Systems Engineering at Iowa State University, is heading up a project to introduce PGC systems into conventional corn and soybean operations. Since 2021, an interdisciplinary team of scientists, engineers, educators, private industry experts, university students, and farmers funded by USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture have worked on making year-round perennial groundcovers the norm for Midwestern U.S. farmland.

The group is called RegenPGC, and central to their approach is developing and minimizing production risks to farmers using PGC systems.

“A PGC approach has lower management requirements, which could enable widespread adoption of cover-cropping systems critical to achieving measurable differences in large-scale environmental issues,” Raman says. “Our vision is to create well-adapted PGC systems for a range of farm operations that require low labor inputs, provide equal or more ecosystem benefits than conventional cover cropping approaches, increase row crop resiliency, and have similar economic profiles.”

Exploring PGC Potential

At the outset, the RegenPGC team wondered what would happen if a PGC was planted between corn rows and remained living for multiple years, rather than terminated like traditional cover crops often are.

Raman says if growers can manage the perennial cover crop’s competition successfully enough, there will be no significant yield loss in the main crop. The key, according to Raman, is to find perennial covers that are complementary in space and time, to minimize competition.

Potential PGC Species

Several other species besides Kentucky bluegrass may be potential PGC candidates, among them Radix Hybrid Bulbosa, or RHb, which also has summer dormancy. It is patented by Radix Evergreen in Aumsville, Ore., and Radix claims RHb does not create a yield drag on cash crops. RHb is seeded in the fall at 130-200 pounds of seed per acre at ¼ inch depth with a timed-release fertilizer blend, but it is currently priced at roughly $400 for 100 pounds of seed.

The RegenPGC group has had some success with several different species, and Raman believes that in the long term, different species will be optimized for different locations. Regardless of the species, they must all possess similar criteria:

- Complete summer dormancy or the ability to be easily suppressed with herbicides or otherwise easily suppressed without being killed outright

- A shallow root system to avoid below-ground competition

- Low-growing

- Shade tolerance

- Adaptation to overwintering.

“Suppression is critical to making the whole system work”, Schlautman says.

Researchers found early summer dormancy or complete suppression of the PGC around corn emergence is critical to the success of integrating perennials because of a phenomenon in corn known as shade avoidance response.

Research by Cynthia Bartel of Iowa State University has found that shade avoidance response results from a low-red to far-red light shift, impairing early season plant growth and decreasing yield. Even competition during early development stages of the crop can result in significant yield reductions.

“It can be considerable yield loss if we don’t get that step right,” Schlautman says. “The group is working hard to figure those things out, but it’s a risk for growers trying it for the first time.”

The idea of using PGC, or perennial living mulches, as they are sometimes called, is not new, by any means. They have been used in orchards and vineyards for some time. But the idea of integrating perennials into annual cropping systems makes the concept unique.

“We are a corn growing region just like Iowa,” says Brandon Schlautman, who grew up in central Nebraska and is currently a RegenPGC research leader at the Land Institute in Salina, Kan. “Our region was previously diverse perennial prairie ecosystems capable of filtering water, carbon nutrient cycling. We want to get back into covers and introduce perenniality into our commodity grain systems.”

Professor emeritus Kenneth Albrecht worked with integrating Kura clover into row crop systems while at the Univ. of Wisconsin for several years, beginning in the early 2000s. He and his researchers were able to successfully suppress the Kura clover early in the season with glyphosate without killing the clover, due to its rhizomatous characteristic.

“Suppression is critical to making the whole system work…”

Kenneth Moore, Shuizhang Fei and other colleagues at Iowa State University have been working on Kentucky bluegrass and other cool season grasses as PGC candidates for about 15 years. Schlautman says that this Kentucky bluegrass type is an old cultivar that has the summer dormancy trait, not the popular turf grass type that has been selected to remain green during the summer.

Searching for Ideal PGC

After considering many options, the RegenPGC team decided to focus initially on summer-dormant Kentucky bluegrass since Iowa State University had already been researching it for several years. It has all the traits the group was looking for in an ideal PGC (see sidebar).

Strip-tillers who have worked with perennial crops — like alfalfa, for example — realize that perennials are naturally slow to establish. The same is true for Kentucky bluegrass, as well as the other perennial groundcovers considered for use in PGC systems. Under experimental conditions especially, greater attention must be given to controlling as many factors as possible when establishing Kentucky bluegrass to assure an adequate stand.

CORN EMERGENCE. Suppression of PGC is critical to success of the system. Photo by: Regen PGC

Erin Haramoto, professor at the Univ. of Kentucky, is leading a group of graduate students to identify establishment factors and management practices, including herbicide selection. Because Kentucky bluegrass is small-seeded and slow to establish, early weeds are especially a problem.

On Sept. 18, 2023, Haramoto and a graduate student planted Kentucky bluegrass with a seed drill into tilled plots, along with a nurse crop of oats. This method assumes that an early crop — wheat, for example — has already been removed to permit early tillage. Because of the dry weather, overhead sprinkling was applied. Following planting, they sprayed glyphosate over all the plots to control existing weeds and followed up post-emergence with dicamba, either spring-applied only or fall- and spring-applied. Sub-plots were treated with selected pre-emergence herbicides. According to Haramoto, the pre-emergence broadleaf mesotrione herbicide, sold under the trade name Callisto, applied in the fall was most effective.

Soil moisture conditions remain an important factor in fall-planted Kentucky bluegrass establishment. When moving from experimental plots to field conditions, the challenge becomes much greater.

PGC TRIALS. Mid-season corn grows simultaneously with Kentucky bluegrass in an experimental plot. Photo by: Brandon Schlautman

“When the fall is dry and hot it’s very difficult to get Kentucky bluegrass established, especially in places like Nebraska or where irrigation is greatly reduced,” Schlautman says.

To compound the problem, the lack of winter moisture may not only reduce Kentucky bluegrass establishment but also create competition between the perennial and the subsequent corn crop.

“A couple of years back, we came out of a really harsh winter drought, so the grass probably did use some of the water over the winter,” Schlautman says. “There was probably water stress for some of that corn before we even planted the crop, so it’s a complex system.”

No-till drilling is the most common method of seeding Kentucky bluegrass.

On-Farm PGC Trials

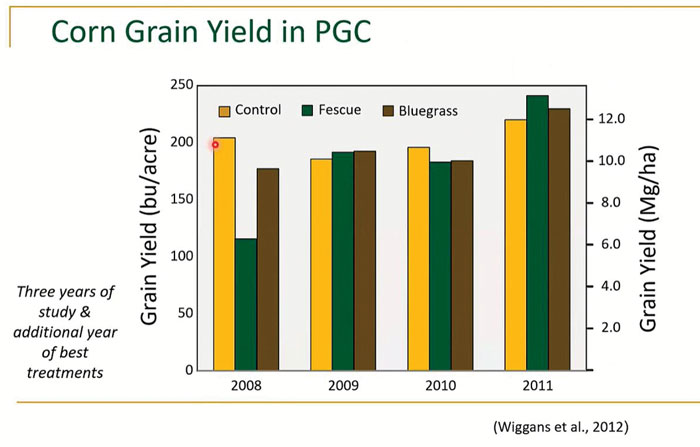

Yields trialed under established PGC conditions initially dipped, but once researchers successfully figured out timely PGC suppression to minimize the shade avoidance response, corn yields in successive years were comparable to conventional yields.

Christopher Gaesser of Lenox, Iowa, farms in southwest Iowa near the Missouri and Nebraska borders. He and his father, Ray, farm 5,400 acres of corn and soybeans, along with cereal rye for cover crop seed.

Christopher Gaesser outlines the steps they have taken over the past 4 years of on-farm PGC production. This will be their 5th crop season working on it. Currently the plot is about 3 acres. He started with a couple of different grass species, but most were too competitive.

YIELD IMPACT. Corn yields with established perennial groundcover (PGC) initially dipped, but once researchers successfully figured out timely PGC suppression, corn yields in successive years were comparable to conventional yields. Source: Wiggans et al, 2012

“We really only have the bluegrass left,” Gaesser says. “I suggest picking older Kentucky bluegrass varieties before they started selecting for more heat tolerance for lawns. It goes dormant quicker and more easily.”

The plot was originally planted with a no-till drill in late September right after corn harvest. Good moisture helps with initial establishment, Gaesser says. He had almost ideal conditions for the Kentucky bluegrass germination and establishment. They seeded it early enough for it to get established in the fall and had enough moisture to get an even stand and a good start.

“We do not strip-till as our operation has a lot of contouring, making that hard to do,” he says. “When we plant soybeans, we don’t do anything differently. We plant with a no-till air seeder and suppress the grass to let the beans get a head start. Originally we had done the same thing with the corn. However, it had a much harder time with the competition, and so in 2023, we sprayed 6-8-inch-wide strips in the fall and then planted into that in the spring. That method worked out a lot better, and the corn performed better in that system.”

The first year the soybean yields were equal to the rest of the field. The second year Gaesser rotated to corn and planted without strips, and yields did not do as well.

“A perennial groundcover approach has lower management requirements, which could enable widespread adoption of cover cropping systems…”

“Even with the grass suppressed, the grass created too much competition with the corn, and it was not good,” he says. “The 3rd year the soybeans were about 25% worse than the rest of the field. The soybeans had some drought stress, and the grass used some of the moisture we needed for the crop. It wasn’t a great year overall anyway. Last year the corn was 10-15 bushels less than the field average. That field averaged about 220 bushels per acre, so still not bad overall. Spraying strips for the corn really helped it.

“We are still running the trials. It is a work in progress. I knew the system would not be something that we could just figure out to work great right away, as it adds a lot of complexity and management decisions to the system.”

All of the RegenPGC participants acknowledge the difficulties of the system but are confident they are on the right track.

“With perennial groundcovers, farmers can continue to leverage the amazing yield gains made through corn and soybean breeding and agronomic research, while also protecting the environment on their farm, in their community, and downstream,” says Sara Lira, research scientist at Corteva Agriscience and RegenPGC commercialization theme leader.