When Jon Stevens started transitioning from conventional tillage to no-till soybeans in 2013 and eventually strip-till corn in 2015, failure was imminent if you asked his Rock Creek, Minn., neighbors.

“I always joke, I’m in the capital city of ‘It don’t work here,’” Stevens says. “I’m strip-tilling and many of my neighbors still say, ‘It simply can’t work here.’”

With a learn-by-doing attitude, Stevens started proving that strip-till, no-till and cover crops could work on soils that he says are described as “ick” by the University of Minnesota.

“Our farm is located in a spot where 3 glaciers came together, threw up and left us with a bunch of rocks,” Stevens says. “In a full tillage system, our soil would shed water like a duck’s back. Low organic matter, low CECs and compaction like concrete. If you want to build a road here, just knock off the top couple inches and lay down your asphalt.”

Strip-Till Creativity

Stevens is a fifth-generation farmer who grew up on a small dairy farm, but he was essentially starting from scratch with conservation practices after decades of conventional tillage. He couldn’t afford to break the bank on fancy, new equipment, so he got creative instead, piecing together his first strip-till rig in 2015 with an old Sukup row cultivator. He extended the shank on the cultivator and attached 8 row units to an Ag Systems caddy with a Montag dry fertilizer box on it.

“It worked well, except I realized that for the number of rocks we have, the unit wasn’t heavy enough,” Stevens says.

He tapped into his imagination, building a more robust strip-till machine the following year out of an old 8-row Hiniker row crop cultivator.

“It already had a chisel plow shank, a nice lead coulter and depth gauge wheel,” Stevens says. “All I needed to do was add row cleaners. I used some receiver hitch-pin tubing and mounted the row cleaner in the middle. I also modified the brackets that hold the depth gauge wheels by flipping them upside down and lowering them. I added berming blades off our old DMI disc ripper. For the fertilizer delivery system, I used some old stainless-steel milking pipeline that’s great for dry fertilizer application, and we still attach it to the Ag Systems caddy and the Montag tank.”

SPRING STRIPS. Jon Stevens of Rock Creek, Minn., makes strips in the spring while applying K, urea and gypsum ahead of corn with his B&H strip-till shank machine.

Before planting corn with his White 9222 planter, Stevens bands 50 pounds of potassium (K), 100-200 pounds of urea and 60 pounds of gypsum about 7-8 inches deep with his newer B&H shank strip-till bar in the spring because his highly erodible soils are prone to blowouts in the fall.

“Spring strip-till is nice because it gives us that fracture in the soil, makes a nice seed bed and puts nutrients down without worrying about leeching over the winter,” he says.

Cover Crops

Stevens began integrating cover crops into his system around the same time he started strip-tilling. Hypothetically, if he had to get rid of only one — strip-till or cover crops — Stevens’ strip-till rig would be on the side of the road with a “For Sale” sign on it tomorrow morning.

“It would be a tough decision and I’d have a lot of crying nights because they’re both wonderful tools,” he says, “But if I had to get rid of one, it would be strip-till because I know over time, I could get the cover crops to do the tillage work for me. And the cover crops will provide fertility and everything else I’m looking for long term.”

Stevens uses multiple species, including alfalfa, hairy vetch, radish, buckwheat and annual ryegrass. And just like with his strip-till rig, he takes an economical approach to cover cropping.

“There are the big guys with millions of dollars, and I’m just the guy that’s welding up a Chevy,” Stevens says. “I don’t have the money or time to build an interseeder. I broadcast the cover crop seed with a 6-ton Willmar spreader in corn around V3-V4. I just measure a couple 50-pound bags, dump it in there, and it works fantastic.”

MIXING IT UP. Stevens broadcasted this grazing mix of hairy vetch, radish and buckwheat around V3-V4. “It works really well with early rains because if we wait until July, it gets dry, and the seeds just lay there until later in the fall,” he says. “The cover crops are part of our rotation. Instead of calling it a cover crop, it’s called a hay field.”

Stevens has learned just as much from failure than success with cover crops. For example, he planted non-GMO soybeans into a green sod field once, which ultimately resulted in a failed soybean crop. In the future, Stevens says he’ll apply a burndown treatment to the living cover before planting into it.

Integrating Livestock

“About the same time, we got serious with strip-till and cover crops, we started reintegrating cows back into our operation as another way to really leverage the benefits of our cash crop rotation and see if we can improve soil health,” Stevens says. “I’m really trying to improve my nutrient management, and the cows are another tool to do that.”

“The cow’s urine is full of N credits. That’s why your dog burns the lawn when they pee in the same spot…” – Jon Stevens

Stevens solves a lot of problems on his farm — like low soil fertility levels, disease and insect pressure — by grazing livestock on his cover crop mixes. He aims to rotate 30-acre grazing paddocks every 3 years into corn and capture the nutrients in the soil to raise a more profitable crop with lower inputs.

“The fields right next to our current pasture are both corn fields,” Stevens says. “Once the combine rolls, we’ll move the cows into those fields to get as much grazing credits off the corn residue as we can and then move them back to pasture for the winter.

“The cows can produce a lot of N, P and K, and so does the crop that they’re eating,” Stevens adds. “The cow’s urine is full of N credits. That’s why your dog burns the lawn when they pee in the same spot.”

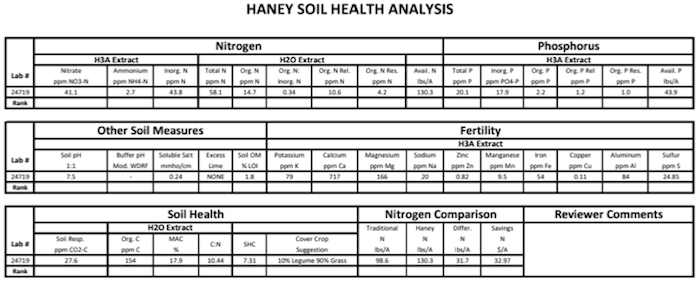

SOIL TEST. A recent Haney soil health analysis report shows over 43 pounds of available phosphorous and $32.97 nitrogen savings per acre on Stevens’ farm. He says his soil fertility levels have increased significantly since implementing a cover crop grazing system.

Stevens has the numbers to back it up. A Haney soil test pulled in 2023 showed 130 N credits in his soil, although he says not all of that was just from the pure soil itself, as there was some fertilizer in it. It also showed 43 pounds of available phosphorous (P), reinforcing his belief that retail P is overrated.

“Those cover crops have built up the P levels in my soil without me even applying any P,” he says.

Quantifying Profitability

Stevens believes farm profitability doesn’t necessarily mean being the highest yielder.

“Peak yield doesn’t always make the most money…” – Jon Stevens

“All these guys who talk about big yield, I don’t care,” he says. “I want my money back. Peak yield doesn’t always make the most money.”

Stevens became more profitable with strip-till almost immediately by cutting P, K and sulfur application rates in half, saving an estimated $40 per acre on tillage costs alone and $100 per acre total. He has some advice for strip-till beginners who are worried about a yield hit in year 1.

“It just comes back to checking the basics,” Stevens says. “Make sure you don’t have air pockets, you’re not trenching too deep, and your berming discs aren’t creating water paths next to the berm. I can’t fathom, if you do the basics, how you can lose money going from conventional tillage to strip-till.”

As Stevens continues to buck the local trend with conservation practices, his goals moving forward include lowering herbicide costs and adding micronutrients to his fertilizer package, with hopes of elevating his yields to new heights in an unconventional way.

Integrating Cattle & Crop Rotations with Strip-Till

Click here to watch Jon Stevens’ presentation from the 2023 National Strip-Tillage Conference. The innovative strip-tiller details his systematic approach to building soil health using cattle and shares results from on-farm trials to show how farm profitability doesn’t always equate to being the highest yielder.

“I don’t know if it’s doable, but if I can put a test plot aside, and be the first guy in our area to have a 300-, 350- or 400-bushel corn crop, that would be great,” Stevens says. “Me, the weirdo in the neighborhood with the ugly fields is also the guy who is known for the high-yield test plot? Now that would add a comedic value that you just can’t buy.”