David Legvold is many things: a Strip-Till Innovator and Hall of Famer, a teacher, a student and, of course, a farmer. For over 40 years, he’s farmed in Northfield, Minn., alongside his wife, Ruth, and sons Mike and Mark. Both the Legvold sons became teachers in the footsteps of their father, and it’s this connection to education that seems to have shaped the family’s outlook on farming. Legvold approaches all aspects of farming as an opportunity for experimentation, and for the past 2 decades he’s directed that curiosity towards strip-till.

2-Year Plan

Current operations on Legvold Farms can be viewed as a 2-year cycle. In the fall, after soybean harvest, a cereal rye cover crop is planted with a 25-foot no-till drill. In the spring, when the rye comes up, a 5-inch-wide by 8-inch-deep zone is tilled and fertilized with 40 pounds of nitrogen (N), plus phosphorous (P), zinc, sulfur, and potash, air injected into the strip. Corn is then planted green into the rye, which is later chemically terminated and used as weed-preventative mulch.

Later in the season, when the corn is about a foot high, it receives a side dressing of 100 pounds of N via a 12-row liquid injection system. A cover crop mix of ryegrass, rapeseed, tillage radish, clover and kale is then broadcasted from a pair of seeders attached to the same 12-row fertilizer injector. The cover crop mix emerges and is growing well by the time corn is harvested in the fall, and the cover crop and corn residue protects the soil during the winter. In the spring, soybeans are drilled directly in, and the cycle begins again.

“Cover crops are a wonderful way to assist in the controlling of weeds,” Legvold says. “It also enhances the biology of the soil by making it a hospitable environment. One summer day, when the sun was at its highest, our soil temperature was 116 degrees on a field without cover crops. It was only 84 degrees on the field with cover crops. Soil biology behaves a whole lot better if it’s not too hot.”

“Unless your tractor time, your fuel and your labor are free, the extra passes will decrease your bottom line…”

The Legvolds’ cover cropping method was notably influenced by on-farm research done by St. Olaf College students, who studied interseeding young corn on Legvold Farms. Their findings led Mark Legvold to rig up their own seeders, using off-the-shelf salt spreaders. He mounted and wired these onto the N applicator, gauged them down, and experimented with them until he dialed in the appropriate pounds per acre rate. Now, seeding and sidedressing can be done in a single pass, efficiency directly attributable to the Legvolds’ willingness to conduct their own on-farm research.

“I’m a lazy farmer, I like to do 2 things at once,” Mark Legvold says. “I thought that it would be wise to do 2 things at once in the field, cut down on our fuel consumption and add the cover crop seed at the same time. The whole process of adding the 2 salt spreaders cost about $2,200 for the machinery, a little bit of wiring and some fun experimentation to make sure that we got the pounds per acre down based on the speed that we apply our nitrogen.”

Strip-Till Origin Story

David Legvold’s initial foray into strip-till coincided with the development of the SoilWarrior. Mark Bauer, who would go on to launch Environmental Tillage Systems, farmed in nearby Faribault, Minn., and Legvold had a front row seat to the building of the SoilWarrior prototype. Legvold Farms was used as one of the trial locations for the prototype, and for 3 years, the farm became part of a working experiment in strip-till adoption. In 2010, Legvold purchased his own SoilWarrior, an 8-row model with a single coulter and dry fertilizer cart. It was a substantial investment, but one backed up by several years of practical research, and Legvold was now dedicated to making the full switch to strip-till.

At the time, the SoilWarrior cost $76,771, and then required a suitable GPS upgrade, which ran another $20,930. When counseling other farmers on making such a big financial leap, Legvold says to consider the model of the 3-legged stool. The first leg is government assistance. The second is a reliable banking partner. The third is salable equipment. If a farmer is going to take the plunge into a new tillage system, at a certain point they just need to commit, and a shed full of old plows and unused machinery is better off sold than being left to rust, Legvold says. He managed the purchase with aid from a conservation stewardship contract and has never looked back.

“The conservation stewardship contract was a boon because that yielded us $138,000, so the machine was paid for, and I even had enough money left over to take Ruth to Dairy Queen. What a deal,” Legvold says.

Sorting out guidance was not as straightforward for Legvold. He had a perfectly good 4650 John Deere with only about 4,400 hours, but it needed a better guidance system for strip-till. The solution came from the local Case IH dealer, who sold Trimble systems, fully integrated and working off the tractor’s hydraulics.

“The conservation stewardship contract was a boon because that yielded us $138,000, so the machine was paid for, and I even had enough money left over to take Ruth to Dairy Queen…”

Unfortunately, Legvold Farms was located on a Verizon “switch border.” Sometimes, inexplicably, a cell phone call would be dropped just by crossing the yard, or guidance would shut down in the middle of working a field. The problem was that the cell signal was being switched between Mankato, Minn., to the south and St. Paul, Minn., to the north; Legvold Farms was unfortunate enough to be stuck in between.

Cell phone bridge technology was the answer, and, along with switching to AT&T, Legvold ended up subscribing to the DigiFarm platform. Pinging off cell towers instead of the less stable satellite link, DigiFarm was both reliable and accurate for Legvold’s operation. Digifarm can dial in location to sub-centimeter, which is miraculous compared to the crude geolocation of years earlier, and invaluable for strip-till, Legvold says.

Another early strip-till challenge for Legvold came from the dry fertilizer system. Legvold used to purchase his fertilizer from a company that used a liquid additive in its dry fertilizer mix. This left the pelleted mix sticky, and prone to clogging up the lines. This was mitigated by the addition of a run/block monitoring system, sensors that signal the cab when a particular line is plugging up. Being able to stay alert to trouble helps with application consistency, and saves time and aggravation in the field.

Soil Health Mission

A huge benefit of Legvold’s switch to strip-till has been less time in the tractor, which translates to less dollars spent. Rather than high yields, Legvold is more concerned with money saved — on labor, equipment hours and fuel. He can use 6/10 of a gallon of fuel per acre with a single pass of the SoilWarrior, as opposed to the 6-9 gallons required for multiple traditional tillage passes.

Legvold’s switch to strip-till has also boosted his soil health. He considers it a life mission to enhance the organic matter in his soil, and few things are as detrimental to that mission as the traditional moldboard plow.

He cites an experiment done by Iowa State College in partnership with the USDA that tracked carbon emissions from recently tilled fields, using various practices. Moldboard plowing was by far the greatest emitter. Plowing incorporated oxygen into the soil, which allowed aerobic microbes to flourish. These microbes set about consuming the organic matter in the soil, and producing carbon dioxide as waste. In the 24 hours following a conventional plowing, an acre might emit more than a metric ton of CO2, exponentially more than is released by other tillage means, Legvold says.

Manure Application Study

A healthy soil microbiome has tangible real-world benefits. Legvold worked with David Mitchell, an Iowa State student, to study the effects of applied manure on the bacterial levels of surface water. Over a 3-year trial, hog manure was applied to 3 test fields. One field received no manure, the second received 1,500 gallons, and the third field received 7,000 gallons. The drainage tile from the fields was segmented so that it could be sampled individually.

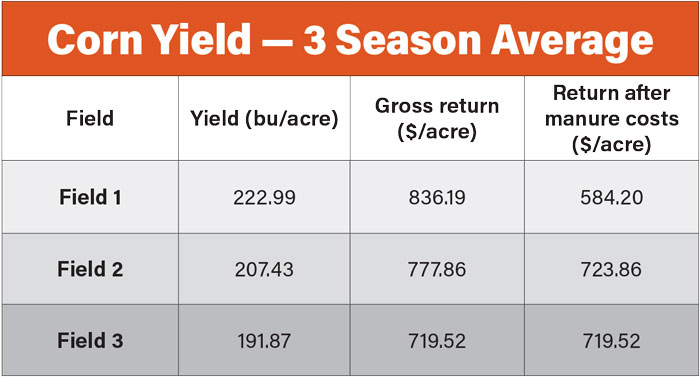

MANURE STUDY. In one of Legvold’s on-farm trials, field 1 received 7,500 gallons of hog manure, field 2 received the correct agronomic rate of 1,500 gallons and field 3 received no manure. Although field 1 had the greatest yield, it also delivered the lowest ROI after factoring in the amount of money spent on manure. David Legvold

Mitchell ran two tests at once, sampling for E. coli, but also measuring soil nutrient retention. The nutrients, as might be expected, were quite disproportionate at the highest level of manure application, with both NO3 and PO4 found in excess. Stalk testing also revealed nitrate as 5,822 ppm from the fields with highest manure use, well outside the expected range of 700 to 2,000 ppm. This extra nitrate, instead of being incorporated into the soil, would end up either volatizing off or leaching into the ground water, utterly wasted.

Even more interesting, though, were the E. coli test results, Legvold says. Even in samples from the field with highest application rates, the excess hog manure didn’t equate to elevated levels of bacteria in the water, as might be expected. Why? It was the native microbial biome in the relatively undisturbed strip-tilled soil that made the difference. These beneficial microbes preyed upon the E. coli, and reduced it substantially before it could infiltrate the ground water. Healthy soils meant safer water.

Of course, for most strip-tillers, things often come down at least in part to money. While the heaviest manure application did amount to a slightly increased yield, the extra bushels did not cover the cost of the extra manure. That sample field was ultimately the least profitable of the three. While the experiment had clear implications about manure application, it showcased the resiliency of strip-tilled soils as well.

Value of Multiple Passes

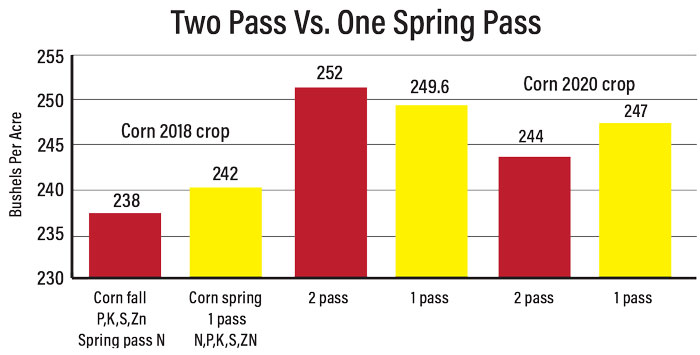

A similar experiment in profitability was carried out by Legvold with the aid of students from St. Olaf College, Carleton College, and the University of Minnesota. It studied the potential benefits and disadvantages of a 1-pass vs. a 2-pass crop system. In 2 out of 3 study years, a 1-pass system, where spring tillage and fertilizer application were combined, resulted in better yields. In the other year, the extra yield from the 2-pass system didn’t offset the extra cost of having to take the tractor back into the field a second time. A similar result came when the prospect of a spring zone refresh was studied. The time and effort required ultimately did not equate with any financial gain.

ONE PASS VALUE. Legvold compared the profitability of 1-pass and 2-pass strip-till systems. The 1-pass system (247 bushels per acre) was 3 bushels better in 2020. “Is it worthwhile to haul the machine out and make extra passes in the spring? I decided, since I’m a cheap Norwegian farmer, it’s not worth it.” David Legvold

“Unless your tractor time, your fuel and your labor are free, the extra passes will decrease your bottom line,” Legvold says. “It may buy you an extra day of dry time because you fluffed the zone and dry things out. But the real costs are really variable because all of your farms are way different than our farm. But I encourage you to do your own research.”

Close collaboration with local colleges and universities is a hallmark of Legvold’s approach. For those strip-tillers skeptical about working with colleges or perhaps unwilling to be told what to do by students, Legvold says that’s the wrong way of looking at things. Students and research partners are there for support, and to inform a farmer’s decisions. They’re allies rather than antagonists and can be enormously useful, Legvold says. He has a rare appreciation for the process of learning, and his 20-plus years of strip-till experience is emblematic of that.

“We’ve found that there are things that we can do to help us care for the environment, care for our soil, and still grow robust crops,” Legvold says. “Many people look for the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow on their farm. However, some years you’re OK, some years not so OK. But I have found that when you use strip-till, you’re pretty close to finding the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.”

Top Takeaways from Strip-Till Trials

Click here to watch David Legvold’s 11th Anniversary Lecture at the 2024 National Strip-Tillage Conference. The original Strip-Till Innovator shared data and observations from dozens of trials on his Northfield, Minn., farm.