Farm profitability and environmental stewardship can go hand-in-hand when planting cover crops, according to Purdue University’s Shalamar Armstrong.

Armstrong, an associate professor of agronomy at Purdue, recently worked on a multi-year research project to determine how precision planting cereal rye and Balansa clover cover crops could affect nutrient uptake and corn yield.

The experiments, conducted in collaboration with Amir Sadeghpour at Southern Illinois University and Andrew Margenot at the University of Illinois, took place on working farm fields in central Illinois and southern Indiana. The project was funded by a research and education grant from the North Central Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program.

Precision Trials

Armstrong and his team precision planted cereal rye and Balansa clover, a species proposed as an overwintering alternative to cereal rye. The control plots were drilled with each species of cover crop, while the precision plots had alternated 30-inch-wide rows of the cover crop and 30-inch-wide rows skipped for the future no-till corn crop.

“We stopped up the drill with duct tape — very economical,” Armstrong says, “It allows me to see if I can plant more strategic rows with less seed and get the same performance.”

“With a 50-75% lower seeding rate per acre, we’re getting the same performance…”

Seeding rates were reduced with the precision plots. The full rate for cereal rye was 35-40 pounds per acre, with rates for precision planting at 50%. The full rate for Balansa clover was 6 pounds per acre. The researchers used rates of 100%, 75% and 50% for the clover precision trial.

The cereal rye and Balansa clover were planted Sept. 11. The cereal rye was terminated in early April, while the Balansa clover was terminated in late April or early May. The researchers used glyphosate and 2,4-D for termination. Armstrong says they tried roller crimping with the planter in 2020, but within 1 week, the cover crops were standing again. Some plots were terminated 2 weeks before planting, while others were planted green.

Illinois Results

In 2021, Armstrong says there was no difference in the amount of biomass produced by the Balansa clover seeded conventionally, precisely and at reduced rates in the central Illinois field. The precision-planted cereal rye produced slightly more biomass than the clover, but the amount was not significantly different, according to Armstrong.

Armstrong says the clover averages 30 pounds of N per acre, while the rye is approximately 50 pounds per acre.

“With a 50-75% lower seeding rate per acre, we’re getting the same performance,” Armstrong says. “Depending on your system and soil type, you can play around with that seeding rate and probably get the same performance. That’s something to consider.”

The carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio and its impact on yield was another factor Armstrong took into consideration. C:N ratios indicate how fast the plant matter will decompose and release nutrients. Ahead of corn, no-tillers want the N to release quickly. Armstrong says the lower the ratio, the faster the N release will happen. In 2021, all four Balansa clover fields had an approximately 10:1 C:N ratio, while the cereal rye plots were about 18:1 across the board.

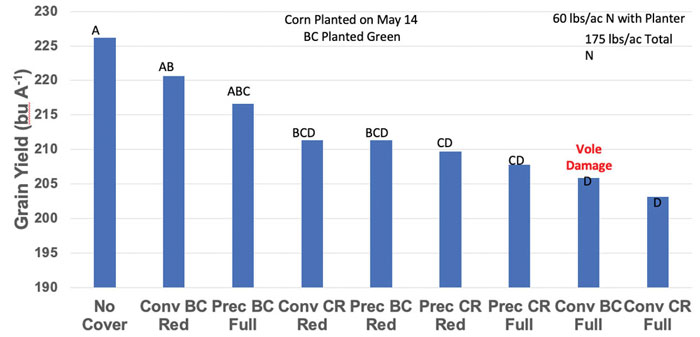

Armstrong says the corn no-tilled into the fields with a reduced rate of conventionally seeded Balansa clover and the full rate of precision seeded Balansa clover yielded similarly to the field with no cover crop. The corn was planted green into Balansa clover May 14. The control field showed the highest corn yields, above 225 bushels, while the no-till corn in the clover plots yielded 216- 220 bushels (see graph 1). The field with a reduced rate of cereal rye produced 211-bushel per acre corn.

GRAPH 1. 2021 corn yields from the central Illinois plots in Armstrong’s study ranged from about 226 bushels to 203 bushels per acre. Corn no-tilled into the fields with a reduced rate of conventionally seeded Balansa clover and the full rate of precision seeded Balansa clover yielded similarly to the field with no cover crop. Shalamar Armstrong

“It’s not significantly different, but it may be numerically different, and it may be financially different,” Armstrong says. “I’m not going to say it’s not, but I do note that this is what we normally would do — full-width drill at the full rate of cereal rye. If we have Balansa clover at a reduced rate or precision planted, we are getting yields that are more competitive to the non-cover crop control. In my book, we’re moving the needle.”

Armstrong also notes that the corn no-tilled into the Balansa clover at the full rate likely would have yielded in the range of the control, had the field not had significant vole damage.

Indiana Results

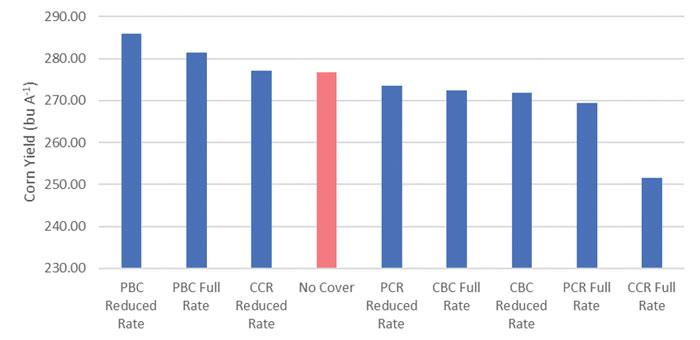

Armstrong also analyzed 2022 data from the southern Indiana plot. There was more Balansa clover biomass than cereal rye biomass across all seeding rates and methods (see graph 2).

GRAPH 2. In 2022, corn no-tilled into the reduced rate, precision-drilled Balansa clover yielded around 285 bushels per acre in the Indiana plot. The second-highest corn yield — 281 bushels per acre — grew in the full rate precision-drilled clover. Shalamar Armstrong

“We can get more with less,” Armstrong says. “We have 73 or so pounds upwards to 90 pounds per acre of N in the clover biomass. For the cereal rye, you’re looking at about 38 pounds of N per acre in the biomass.”

Corn no-tilled into the reduced rate, precision-drilled Balansa clover yielded around 285 bushels per acre. The second-highest corn yield — 281 bushels per acre — grew in the full rate precision-drilled clover. No-till corn in the reduced rate of cereal rye, which was about 75% of the typical seeding rate, yielded about 276 bushels per acre, about the same as the control field with no cover crops.

“What we’re seeing is a trend of lower rate, equal or greater yield, and precision planted, lower rate equal or greater yield,” Armstrong says.

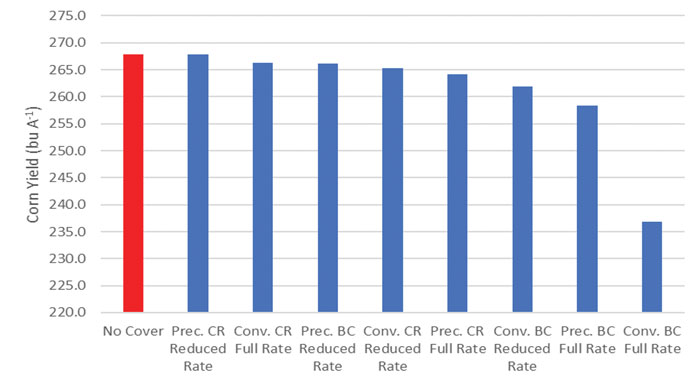

The 2023 drought affected corn yield in all the southern Indiana plots (graph 3). The field without cover crops and the one with precision-planted, reduced-rate cereal rye both yielded about 267 bushels per acre. Armstrong says he would have terminated cover crops earlier if he’d known drought was ahead.

GRAPH 3. The 2023 drought affected corn yields in the southern Indiana plots. Armstrong says he would have terminated the cover crops earlier if he could have predicted the drought, as the cover crops took up water and fixed nitrogen, affecting corn emergence. Shalamar Armstrong

“We had this massive cover crop growing using water and fixing nitrogen,” Armstrong says, “but because it’s so dry, the decomposition is very slow. It affected corn emergence. In this particular situation, we terminated the cereal rye earlier, so cereal rye treatments are more competitive relative to some of the Balansa clover treatments, but still this reduced rate is most equal relative to the non-cover crop control.”

Trial Results

Armstrong says the 3 years of data from the study show lower cover crop seeding rates positively affected corn yield.

“50-75% lower seeding rate generated the same biomass, same carbon, same N,” Armstrong says. “Precision-planted cover crops at a reduced rate resulted in greater yield potential. When you reduce the rate, you’re reducing the potential for interference with the planter, so you’re reducing the potential for reductions in yield due to stand loss.”

Precision Planting Cereal Rye & Legumes for Increased Yields

Winter-hardy cereal rye is the most popular cover crop choice for no-tillers, but it can cause a yield hit in corn if the right (or wrong) weather comes in spring. In this video from the 2024 National No-Tillage Conference, Purdue University’s Shalamar Armstrong goes into further detail about the findings from the precision-planted cover crop trial and studies comparing maximum return to nitrogen of cereal rye and Balansa clover. Click to watch.

Armstrong says this holds true for both Balansa clover and cereal rye. He also notes that in 2 of the 3 years, corn planted into Balansa clover needed less N than the cereal rye to reach optimum corn yields. In 1 out of 3 years, Balansa clover needed less nitrogen than the no-cover crop control.

“This is management that you adapt in field, whether you’re changing your cover crop species, the rate that you plant them or how you plant them,” Armstrong says. “We have levers that we can pull in our management systems to tighten up the yield gap to make things more profitable in a cover crop system.”